What are the benefits of fairway irrigation and how do you avoid the pitfalls?

Related Articles

Agronomist Stella Rixon looks at both issues here

Given the challenging dry spring and early summer weather in the south-east last year, many course fairways showed drought stress early. This always instigates conversations regarding installation of irrigation. However, there are always justified concerns on how the addition of irrigation might reduce the fairway playing quality. If used poorly, higher than desirable water inputs will produce lush growth, thatch and promote undesirable grass species (predominantly annual meadow-grass).

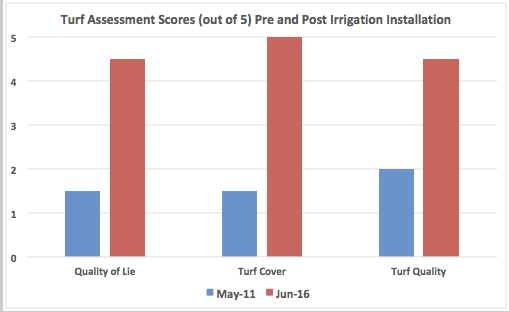

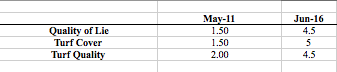

Using a heathland case study, Golf Club ‘X’ is set on free-draining, acidic sandy loam soil. In 2011 the club asked STRI to undertake a turf quality benchmarking study of three of its weakest fairways prior to installation of an automatic irrigation system, to be used from spring 2012. Three 10x10m sample areas were identified on each fairway and assessed for quality of ball lie, grass cover / bare ground and sward species composition, as described below:

Quality of lie – At each of the sample points, three golf balls were thrown within the 10x10m sample point and quality of lie was assessed in terms of both grass behind ball, levelness with surface and balls in divots to determine whether each of the balls’ lie was acceptable or not. A score of one was given for an unacceptable lie, three for adequate and five for a perfect lie.

Turf cover – The amount of grass cover was assessed within the 10x10m sample areas and given a score of one (40 per cent bare ground), three (20 per cent bare ground) or five (no bare ground or divots).

Turf quality – Turf quality was assessed in each 10x10m grid and given a score of one (low), three (moderate) or five (high) based on its uniformity of appearance, density and impacts of bare ground.

Species composition – Percentages of annual meadow-grass, bentgrass, ryegrass and fescue were estimated in each sample grid.

In summer 2016, after four years of using fairway irrigation, the same sample areas on the fairways were reassessed and the results compared.

Results

When first assessed prior to irrigation installation, the fairways were prone to severe drought stress causing significant loss of grass cover and thinned, patchy swards (below left) that were dominated by annual meadow-grass (poa annua).

This grass species is ubiquitous in the environment and highly present in the soil seedbank. It can quickly exploit bare areas left by drought stress, once moisture becomes available again in the autumn, but it also has poor drought tolerance and so dies out again in the summer.

Hence an undesirable vicious circle occurred each year.

Once irrigation was installed, it was used judiciously in combination with overseeding to maintain suitable moisture levels to promote the desirable fine grasses and prevent extreme drought and loss of grass cover, hence keeping the weedgrass poa out.

The second fairway, mid-point May 2011, prior to irrigation installation. Thin grass cover, 60 per cent of which is poa annua and only 40 per cent desirable bent / fescue

The second fairway in mid-point June 2016. It now has 90 per cent grass cover made up of patches of desirable bent and fescue with less than five per cent poa

The 16th fairway sampling area 1 in May 2011, prior to irrigation installation. Patchy grass cover made up of 50 per cent poa annua and 50 per cent bent / fescue

The 16th fairway sampling area 1 in June 2016 now has full grass cover with 90 per cent fescue / bent and only 10 per cent other grasses including poa. Some red thread disease patches but no bare areas except for occasional divots

Steps to success

- Irrigation can break drought induced die-back and poa annua succession cycles.

- It is important to overseed with desirable grass species (dominated by creeping red fescues for dry sites) to fill in a thinned sward and use irrigation to give successful germination, in the absence of sufficient rainfall.

- Overseeding technique and timing are all important to success. Seed must get contact with the soil, which often requires intensive large bore solid tining or hollow coring prior to drill seeding in order to get seed to below the thatch layer. Placing the seed below the thatch will ensure it does not dry out and fail to establish.

- Use irrigation with caution. Too much will result in annual meadow-grass establishment and build-up of thatch.

- Monitor thatch levels via organic matter sampling at the same time and in the same area each year. This will check that irrigation is not promoting thatch accumulation and inform the need for future hollow coring.

- Check moisture levels with a reliable moisture meter. Once established and well-rooted, fine grasses will survive quite happily at moisture levels of 10-15 per cent vwc in the upper 60mm of the profile (as measured with a Delta-T HH2 probe).

- Hydrophobic soil conditions are common where severe drought stress has occurred. Check for hydrophobicity (water drop test) and treat with wetting agent applications preferably prior to overseeding to improve establishment success.

- Occasional feeds might be required to promote sward infill and seedling establishment. Heathland soils are often quite acidic and, combined with low moisture levels, this means there is low microbial activity. Use simple (as opposed to complex / slow release) fertilisers that are readily available to the plant, such as ammonium sulphate or nitrate soluble feeds. Use the latter if soil pH is below 5.0 to avoid over acidification.

Stella Rixon is an STRI agronomist